MITRE CVE Program - the past, the present .. and the (European) future.

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) program is a globally adopted system for identifying and naming cybersecurity vulnerabilities with unique IDs. Established in 1999 by researchers at the MITRE Corporation (a U.S. non-profit R&D organization), CVE was created to ensure that different ..

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) program is a globally adopted system for identifying and naming cybersecurity vulnerabilities with unique IDs. Established in 1999 by researchers at the MITRE Corporation (a U.S. non-profit R&D organization), CVE was created to ensure that different security tools and stakeholders can refer to the same vulnerability in a consistent way.

Each CVE entry corresponds to a publicly disclosed software or hardware flaw, labeled in the format "CVE-Year-Number" (for example, CVE-2025-12345).

MITRE has operated the CVE program since its inception - acting as the primary coordinator and editor of the CVE list - with funding and oversight from the U.S. government (originally through DHS and now its Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, CISA).

Because of this level of funding and official support, CVE has become a de facto global standard for vulnerability identification and tracking. The database has grown to catalog nearly 275,000 vulnerabilities as of early 2025, with roughly 40,000 new CVE IDs assigned each year in recent years (according to this article, I haven't verified the numbers myself, but they sound reasonable).

Another important task taken care of by MITRE is the managing a broad community of CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs) - over 400 organizations worldwide such as tech vendors (Microsoft, Google, Apple, etc.), security firms, and CSIRTs - that are authorized to assign CVE IDs to vulnerabilities in their own products or domains.

MITRE maintains the central CVE database and website (cve.org) where new CVE entries are published and documented. It also oversees related classification efforts like the Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) (a catalog of root causes of vulnerabilities).

In essence, MITRE serves as the steward and editor of the "dictionary" of cybersecurity flaws that virtually all security tools, vendors, and practitioners rely on. Unfortunately this is the point where I have to admit that I didn't come up with this analogy, I stole it from a Reuters article.

The U.S. National Vulnerability Database (NVD) maintained by NIST, for example, uses CVE identifiers as its index and enriches each CVE with additional metadata (CVSS scores, impact, references) - but it cannot catalog a vulnerability that doesn’t have a CVE ID assigned.

All of this is a long-winded way of saying: CVE is deeply embedded in vulnerability management workflows across industry and government: from patch management systems and intrusion detection tools to vulnerability scanners and threat intelligence feeds, CVE IDs are the common language for discussing and addressing security flaws.

Which is one of the reasons why the potential end of the funding for the CVE program was such a shocking, unexpected development. Not just because the financial cost of the contract that's been going around is comparatively small, at atround 29 Million US-Dollars, but because not only the CVE-program itself would be affected. According to Yosry Barsoum (MITRE’s Vice President for the Center for Securing the Homeland), this loss of support covers both the CVE List and associated efforts such as CWE.

Public reporting indicates the contract was not renewed due to broader budget cuts and policy shifts. The current U.S. administration has implemented an initiative to slash funding for various cybersecurity programs - one report describes DHS/CISA undergoing "significant cuts" and letting numerous cyber-related contracts lapse.

The CVE contract appears to have been a casualty of this cost-cutting campaign. At least initially, because at the time of this writing it seems that a horrible end to CVE has been averted, at least for the time being, with the existing contract extended for at least a year.

This gives everyone some breathing space. A breathing space that should be used to take a hard look at what a disruption, or even complete end to CVE, would mean, and what could be done to make such an end less painful for everyone. Which is precisely what I want to do in this post.

Short-term disruption

A service interruption of the CVE program would have impacts on multiple fronts: national vulnerability databases and advisory feeds would deteriorate, tools and products that rely on CVE updates would suffer delays, incident response teams would lose a key reference, and even critical infrastructure security could be weakened.

In practical terms, a freeze or shutdown of CVE means newly discovered vulnerabilities might not receive a CVE ID promptly (or at all). Software vendors and researchers disclose dozens of new flaws every day, and without CVE IDs, there is no standardized way to track or refer to them across different platforms and agencies.

Even for a short period, this could cause confusion and delays: for example, a critical zero-day vulnerability might be announced by a vendor, but if no CVE ID is assigned, some security tools or databases might not record it, and defenders could miss alerts. Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure processes (where CSIRTs and vendors work together to fix issues before public disclosure) could also be hampered if no CVE can be reserved to track the issue.

Timing and prioritization for security teams would also be an issue. Patching decisions often rely on CVE-based metrics (like CVSS scores in the NVD, which are indexed by CVE). If new vulnerabilities don't get CVEs, organizations may struggle to quickly assess whether a new flaw affects them or how severe it is.

In short, attackers might benefit from the chaos: when defenders and software vendors can't efficiently communicate about a bug (because there's no common ID or entry to refer to), adversaries have more time to exploit those gaps.

Once a service interruption would be rectified, problems would not be over immediately. The chances are high that a backlog would have developed - CVE IDs might pile up unissued, and the program would need to play catch-up to assign and publish identifiers for the vulnerabilities that emerged during the downtime.

This backlog problem is something the CVE ecosystem has experienced before during less dire circumstances. NIST’s NVD has struggled with processing delays due to resource constraints.

All of this shows that even a short interruption of the CVE-program would be problematic, highly so. But a long-term one? Much, much worse.

Long-term disruption

Assuming that we would experience a long-term disruption we would increasingly see fractures in the global vulnerability tracking system. In the absence of an official CVE service, we could see a proliferation of alternative vulnerability IDs and databases:

- Some large software vendors (many of whom are CNAs) might start using their own tracking numbers for new vulnerabilities (for example, using internal bulletin IDs or GitHub Advisory IDs as substitutes).

- Security companies and consultancies might offer stopgap proprietary vulnerability tracking services. For instance, a firm could maintain a private list of new bugs and assign its own identifiers for clients. However, these proprietary systems might not be freely accessible or universally accepted, leading to silos of information.

- Open-source projects and researcher communities might resort to informal coordination (sharing details on forums or lists without a standard ID). This lack of standardization would make it much harder to correlate reports; a single flaw could be referenced by multiple names in different places, causing confusion.

Over time, a prolonged gap in CVE could force the cybersecurity industry to attempt a replacement mechanism.

In theory, another organization or consortium could step in to recreate a CVE-like capability. Many CNAs can assign IDs for their products, but without MITRE’s coordination and the central CVE database, those assignments have nowhere official to go. Thus, a long-term outage would likely erode the trust and synchronization that the CVE framework provides.

CVE grinding to a halt entirely

Assuming that we end up in a situation where, for example, funding definitively runs out entirely, the program would shut down. MITRE’s database would freeze at the last issued CVE.

It’s hard to overstate the global fallout of this scenario: as one researcher put it, lack of support for CVE would "cripple cybersecurity systems around the globe" causing "a breakdown in coordination between vendors, analysts, and defense systems - no one will be certain they are referring to the same vulnerability".

In this scenario, we might see competing vulnerability databases emerge (perhaps one backed by industry consortium, others by governments or regional bodies). Different security tools might support different ID feeds, complicating automation.

Over a longer horizon, the world would likely converge on a new standard (the necessity of a common language is such that stakeholders would eventually rally around a solution), but years of effort could be required to rebuild what CVE had provided.

The loss of CVE's neutral, vendor-agnostic stewardship might also shift power to whoever maintains the new list (be it a government or big tech companies), which is very much an important question given the current geopolitical situation.

Quo vadis, EU?

Given the scenario of CVE faltering, a natural question arises: are there existing or alternative systems that can take over the role of CVE, at least partially? In Europe, the focus is indeed on ENISA and national CSIRTs, but their readiness to replace CVE is limited in the immediate term.

Under the NIS2 Directive, ENISA has the mandate to build an EU-wide vulnerability database and support coordinated vulnerability disclosure across member states.

The vision is that organizations can voluntarily disclose vulnerabilities to this European database, improving transparency and mitigation. However, this project is still in development. ENISA has spent the last few years working on policies, methodologies, and preparing the technical platform for the database.

At the time of the revelations that the contract for CVE might be cancelled the platform wasn't available to the general public yet. It was hastily opened to the public after the event, but it's still a work in progress. Thus, ENISA cannot immediately step in with a fully functional "EU CVE".

(On a related note, ENISA's EUVD is hosted on Microsoft Azure. Make of that what you will - but I hope that you see the irony in that, given why the EUVD exists in one of the first places.)

However, ENISA is now a CNA within CVE (as of January 2024), meaning it has a foot in the existing system. If CVE were to shut down, ENISA could theoretically use the structures it has set up for the EU vulnerability database to start tracking European disclosures. ENISA has been maintaining a "vulnerability registry service" since becoming a CNA, to support the EU CSIRTs network's coordination needs.

This suggests ENISA has some infrastructure to record vulnerabilities reported via European channels. In a pinch, ENISA could try to expand this registry to serve as a temporary database for vulnerabilities (at least those affecting Europe).

The challenge would be persuading global vendors and researchers to also report into the EU system - not just EU-based finders. Because vulnerabilities don't respect borders, a solely European database is inherently limited if other countries or companies don't participate.

ENISA's database would be most useful for vulnerabilities in products from European vendors or found by European researchers (since those are the ones ENISA as a CNA covers). It's less clear how, say, a vulnerability in an American-made cloud product would get into the EU database if CVE is offline. ENISA might need to coordinate with other CNA-like bodies internationally to intake such reports.

In absence of CVE, national CERTs in Europe (like CERT.at, CERT-FR, Germany's BSI, etc.) could use their own vulnerability tracking within their jurisdictions. Many CERTs already maintain lists of security advisories. For example, CERT-FR assigns an advisory number (e.g., CERTFR-2025-AVI-xxx) for each bulletin.

These national identifiers could be used to reference issues domestically. But they are not globally recognized the way CVE is. National CERTs could also potentially band together to create a temporary shared ID scheme - perhaps coordinated through the CSIRTs Network (which ENISA facilitates).

This network, established under the EU Cybersecurity Act, allows EU member state CERTs to collaborate. In theory, they could agree on a quick interim approach like "EU-VULN-2025-xxxx" numbers for new discoveries.

The phrase "in theory" is carrying a lot of this however. This "solution" would still be Europe-specific and would require a lot of quick consensus. There is no evidence yet of such a plan being in place; it might only be attempted if it became clear CVE was going to be down for a long time.

Outside of Europe, other players might attempt their own stopgaps. For instance, in Japan, the JVN (Japanese Vulnerability Notes) system tracks vulnerabilities (often referencing CVEs). Japan's CERT could potentially assign their own IDs for issues in Japanese software if needed.

Similarly, regional CERT alliances (like OASIS in Latin America or APCERT in Asia-Pacific) could consider interim measures. But like Europe's case, none have the scalability or authority that CVE has built up.

One more alternative could be an industry-driven initiative. Major tech companies and cybersecurity vendors, who have a vested interest in not letting vulnerability coordination collapse, might come together to fund and maintain a community CVE-like list if the government cannot.

This is speculative, but not impossible - organizations like FIRST (Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams) or standards bodies could help rally such an effort. In fact, the CVE Program has an international Board and numerous private sector partners, which could serve as the nucleus for a community-driven solution.

The catch is, doing this quickly and effectively without the prior infrastructure is extremely challenging. The existing CVE platform and processes took years to mature; replicating them would be a significant undertaking.

In essence, no fully mature alternative to CVE exists in Europe right now, but the groundwork (ENISA's mandate and the CSIRTs collaboration) provides a starting point for Europe to respond. European officials haven't yet issued public statements about the CVE funding issue (likely because it’s unfolding and is primarily a U.S. budget matter), but you can expect concern in EU cybersecurity circles. The situation underscores the importance of the EU's efforts to build its own capacities.

As one EU cybersecurity official had noted in a related context, having a central agency stockpiling vulnerability information can itself be a risk if not managed properly - but now Europe faces the opposite risk of having that central repository (in this case CVE) suddenly go away.

Europe would strive to mitigate the impact via ENISA and CERTs, and in the medium term might accelerate the roll-out of its own vulnerability database. Yet in the immediate term, a CVE outage leaves Europe in a difficult spot, largely in the same boat as everyone else in the global cybersecurity community. Coordination and standardized tracking of vulnerabilities would suffer until either CVE is restored or an alternative is stood up.

Conclusion

The current CVE program's funding crisis presents, without wanting to sound dramatic, a moment of peril for global cybersecurity.

What is at stake is not just a database, an organization, or a contract, but the continuity of a universal language for vulnerabilities that underpins daily cyber defense operations around the world. From global incident response down to local IT patching, the shockwaves of a CVE shutdown would be felt in every corner of the cybersecurity landscape.

For Europe, the situation is yet another wake-up call (.. or at least should be .. given my experience with Europe and information security I'm not holding my breath for things to actually change, but I digress ..) about dependency on external cyber infrastructure, even as the EU works on its own capabilities.

In the immediate future, European entities will be hoping - along with everyone else - that the U.S. finds a swift solution to keep CVE alive, in a more permanent way than the extention of the contract we got right now.

In parallel, Europe's efforts (through ENISA and others) to build complementary systems may need to accelerate, both to assist now if needed and to provide a safety net for the future.

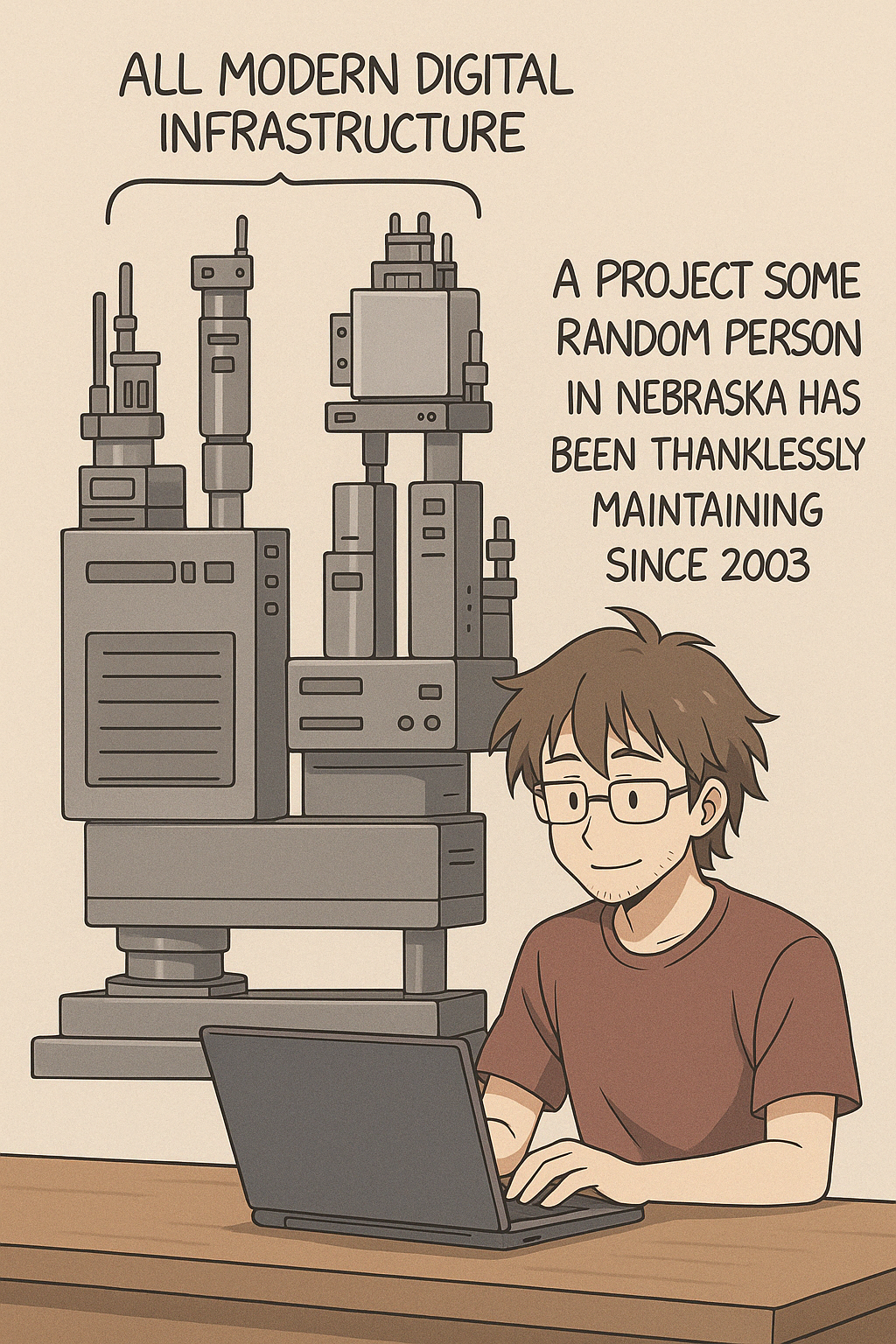

Whatever the resolution, one lesson is clear: the CVE program is not to be taken for granted. It has been called a foundational pillar of cybersecurity and this episode proves that XKCD 2347 doesn't just apply to software:

Going forward, ensuring the sustainability and resilience of such foundational resources - through stable funding, international cooperation, and perhaps governance that spans borders - will be, once more, crucial. It's going to be interesting to see if actions are actually taken this time. Forgive me if I have my doubts.